Depressive Disorders

Introduction

Individuals with cancer are at increased risk for depressive disorders throughout the disease trajectory, with severity ranging from subthreshold to adjustment disorder with depressed mood to major depression. Depression is a clinical condition with hallmark features of low mood and/or loss of interest or pleasure in most or all normal activities for at least 2 weeks duration. The potential overlap between symptoms of depression and cancer/treatment side effects (e.g., sleep disruption, appetite and weight changes, decreased energy) highlights the critical need for provider attunement to the complexity of diagnosing depression in the setting of cancer. Modifying diagnostic approaches using Endicott criteria, particularly in advanced cancer, can help delineate neurovegetative symptoms of depression and cancer/treatment.1

Prevalence rates vary in the literature, owing to differences with respect to assessment approaches and patient reported outcome measures, and disease-related variables such as cancer type, stage, and treatment course. Overall, the prevalence is 24.6% for all types of depression, and 16.5% for major depression2 which is notably higher than the general population rate of 7%.

Table 1. Depressive disorder categories, ICD-10 codes, prevalence, and diagnostic criteria. (* not cited in the literature)

| Depressive Disorder Diagnosis | Prevalence in General Population / Cancer Population | DSM-5 Criteria/Symptoms |

| Adjustment disorder with depressed mood (F.43.1) | 5-20% / 24.7% |

● Emotional or behavioral symptoms within three months of the onset of a specific stressor ● Experiencing distress out of proportion to the stressor which causes impairment in social, occupational, and other areas of functioning ● Symptoms do not represent another disorder or part of normal bereavement |

| Major depressive disorder (F32.0 – F33.9) | 7% / 16.5% |

● Low mood and/or decreased interest in activities for most of the day and at least 4 of the following: ● Significant weight loss or weight gain ● Insomnia or hypersomnia ● Psychomotor agitation or feelings of being slowed down ● Fatigue ● Excessive feelings of worthlessness or guilt ● Difficulties with concentration or indecisiveness ● Reoccurring thoughts of death or suicide ● Symptoms cannot be explained by the physiological effects of a substance or to a medical condition ● Symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, and other areas of functioning |

|

Substance/ Medication-Induced Depressive Disorder (F10.14 – F19.94) |

0.26% / * |

● Significant disturbance in mood evidenced by depressed mood or decreased interest in activities ● Findings from history, physical examinations, or laboratory results indicate that the symptoms developed following the intoxication of a substance, withdrawal from a substance, or exposure to medication ● Symptoms are not better explained by an independent depressive disorder ● The disturbance does not solely occur during the presence of delirium ● Symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, and other areas of functioning |

| Depressive Disorder due to Another Medical Condition (F06.31 – 34) | * / * |

● Persistent depressed mood or decreased interest in activities ● Findings from history, physical examinations, or laboratory results indicate that the disturbance is the direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition. The disturbance does not solely occur during the presence of delirium. ● Symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, and other areas of functioning |

|

Persistent Depressive Disorder (F43.1) |

1.5% / * |

● Depressed mood for most of the time for at least two years (one year in children and adolescents) with at least two other symptoms. ● Low appetite or increased appetite ● Insomnia or hypersomnia ● Low self-esteem ● Fatigue ● Difficulties with concentration or decisiveness ● Feelings of hopelessness ● An absence of symptoms does not occur for more than two months ● There is no presence of a manic or hypomanic episode. Cyclothymic disorder criteria have not been met ● The disturbance is not better explained by schizophrenia spectrum disorders and is not explained by the physiological effects of a substance or medication condition ● Symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, and other areas of functioning |

Click here to view table as PDF

In addition to negatively impacting emotional well-being, functioning, and quality of life, comorbid depression is associated with reduced treatment acceptance and adherence, prolonged hospitalization, lower pain tolerance, and increased mortality. Significantly, people with cancer have three times the risk for suicide than the general population.3 For these reasons, routine screening, assessment, and treatment of depression is regarded an essential component of quality cancer care.

Guidelines

Guidelines established by the NCCN and adapted by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) provide direction on clinical management of depression, outlining the following steps:

- Evaluate all cancer patients for symptoms of depression

- Conduct screening and assessment at clinically meaningful intervals across the trajectory of cancer care (e.g., posttreatment, recurrence, progression)

- Recognize and treat symptomatic patients to mitigate negative emotional and behavioral sequelae

- Refer appropriately

NCCN Guidelines Distress Management Guidelines V.2.20244

ASCO Guideline Adaptation of A Pan-Canadian Practice Guideline: Screening, Assessment and Care of Psychosocial Distress (Depression, Anxiety) in Adults with Cancer

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4090422/

- https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/practice-and-guidelines/documents/depressi on-anxiety-summary-of-recs-table.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4090422/figure/F1/

Li M, Kennedy EB, Byrne N, et al. Management of Depression in Patients With Cancer: A Clinical Practice Guideline [published correction appears in J Oncol Pract. 2017 Feb;13(2):144]. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(8):747-756. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.011072

Screening

Table 2. Validated measures for depression screening for cancer patients.

| Measure | Public Domain | Items/Subscales and Scoring |

|

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) |

Y |

20 items; Ranges from 0-60 Scores < 16 non-depressed; 16-19 mild; 20-30 moderate; > 30 severe in the general population. Scores tend to run slightly higher in advanced cancer population. |

|

Edmonton Symptom Assessment System-revised (ESAS-r) Depression items |

Y | 10 items; Each time is rated on a 0-10 numerical rating scale. While not widely studied, a difference of 1 points is recognized as being a minimum clinically important difference in one international multicenter study |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | N |

14 items/2 subscales of anxiety and depression Depression subscale cutoff scores: 0-7 normal; 8-10 mild; 11-14 moderate; 15-21 severe

|

| Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) | Y | 2 items; Total score ranges from 0-6; Endorsing either item as occurring for more than half of the time or nearly every day ( score of > 2) prompts recommendation for PHQ-9. |

|

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)* *contain somatic items resembling cancer symptoms/treatment side effects |

Y | 9 items and 1 additional unscored question; Depression cutoff: Score of 3 or more on first 2 items and total score of >8 (lower threshold reflects ASCO Guideline Adaptation recommendation) Can result in false positives for advanced cancer patients or those in active treatment with neurovegetative symptoms. |

| Profile of Mood States (POMS-37/POMS-SF) | N | 37 items/6 subscales: tension, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion; Depression subscale ranges from 0-32, with lower scores indicating more stable mood |

| Brief Edinburgh Depression Scale BEDS | Y |

6 Items; Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale; Depression subscale cutoff scores: 4-6 mild; 7-8 moderate; 9-11 moderately severe; 12+ severe |

Click here to view table as PDF

To improve health outcomes, screening needs to be followed by assessment and appropriate referral for individually tailored, evidence-based treatment when indicated. Specialist referral is recommended in cases involving risk for harm, unclear diagnosis, persistent symptoms, complex psychosocial needs, and indication for specialized treatment interventions.7

Table 3. Risk and resilience factors influence the development, course, and recovery from depression

| Risk Factors | ||

| Disease-related Factors | Sociodemographic Factors | Individual Factors |

|

• Cancer Type Brain Pancreas Lung Head and Neck • Advanced/Late Stage • Poorer prognosis • Physical burden • Fatigue • Pain • Disfigurement • Disability |

• Younger age • Inadequate social support • Social Isolation • Socioeconomic status |

• Personal and/or family history of depression • History of substance use disorder • Maladaptive coping–such as substance use, treatment nonadherence • Prior trauma |

| Resilience Factors | ||

|

• Strong social support • Supportive care team • Adaptive coping approaches, such a problem-solving, • Mental/psychological flexibility • Faith/spiritual support seeking social support |

||

Click here to view table as PDF

Evaluation & Diagnosis

Clinicians evaluate and diagnose depression by conducting a clinical interview that incorporates diagnostic criteria, symptom measures, clinical history, and clinical observations. Areas assessed in an interview typically include:

|

• Presenting symptoms, history of onset, and severity • Level of functional impairment • Presence or absence of risk factors • Predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors |

• Personal and family history of psychiatric disorder • Presence of comorbid mental disorders, such as anxiety • Psychosocial factors that may influence health outcomes • Symptoms, side effects, and medications which can mimic mood disorders |

Click here to view table as PDF

To arrive at a diagnosis, thorough evaluation considers the full range of possible conditions presenting as depression, such as:

- Bipolar disorder Hypoactive delirium

- Neuropsychiatric effects of cancer and treatment Substance use

Additionally, standardized interviews, such as the Composite International Diagnostic Interview or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5, are used to systematically assess mental disorders and provide diagnoses according to the definitions and criteria of the International Classification of Diseases and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual.

Treatment

Psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatment interventions for comorbid depression have demonstrated benefits for people with cancer. For people with more severe depression, combined treatment of psychotherapy and medication is recommended. Although some treatment modalities have not been studied in the oncology population or have not demonstrated benefit (e.g., manualized cognitive-behavioral therapy in advanced cancer9) , there is a growing body of literature on effective cancer-specific interventions for depression. Selection of treatment–initially and at follow-up–depends on a variety of factors, including the following:

- Nature and severity of the depression, and response to initial course of depression treatment

- Disease-related factors

- Cancer type and stage • Course of cancer treatment

- Individual factors

- Coping strengths and challenges • Functional status

- Presence/absence of risk factors • Cultural considerations

- Appropriateness of medication side effect profile • Treatment modality preferences

- In case of recurrent depression, history of response • Comorbidities (e.g., chronic pain, trauma history, other to treatment psychiatric conditions)

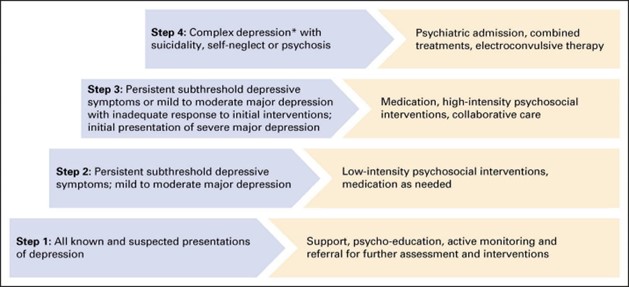

For optimal outcomes, clinical practice guidelines have evolved to recommend a stepwise care approach that tailors treatment delivery based on severity of depression, as shown in the figure below. In addition, increasing evidence favors integration of multidisciplinary Collaborative Care interventions within a stepped care framework for management of depression.

http://www.teamcarehealth.org/ http://impact-uw.org/

Stepwise Support in Cancer11

Table 4. Low- and high-intensity psychological interventions have been developed for individuals with cancer:8

| Low Intensity | High Intensity |

|

● Psychoeducation ● Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction ● Behavioral Activation Treatment ● Problem Solving Therapy ● Self-guided cognitive behavioral interventions ● Structured group physical activity |

● Cognitive Behavioral Therapy ● Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy ● Interpersonal Therapy ● Supportive-Expressive Therapy ● Acceptance and Commitment Therapy ● Behavioral Couple Therapy ● Core Conflictual Relationship Theme |

Click here to view table as PDF

An additional psychotherapeutic intervention designed for those with advanced cancer has demonstrated reduction in depression symptoms:

- Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully http://www.gippec.org/projects/cancer-and-living-meaningfully-calm.html

Pharmacologic Approaches

For practical guidance on pharmacologic interventions specifically for patients with cancer, refer to the ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Data Supplement8, which includes information on prescribing practices, classes of antidepressants for use in patients with cancer, and potential antidepressant drug interactions https://ascopubs.org/doi/suppl/10.1200/JOP.2016.011072/suppl_file/DS_2016.011072.pdf

General approaches for management of depression include the following:8

- Provide psychoeducation and handouts on depression https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/feelings/depression-pdq

- Inform patients about health outcomes of comorbid depression and cancer

- Destigmatize depression by taking a nonjudgmental stance and defining it as a serious health condition; as needed, assist patients and family members with reframing it from a personal weakness

- Rule out potential medical factors contributing to or mimicking depression

- Enlist involvement of family members as needed to provide education and increase patient support

- Review treatment options and engage in shared decision making that incorporates patient treatment preferences

Cultural Considerations in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Depression

Culture can impact how individuals experience distress, and the role of culture in depression after cancer diagnosis is complex. Thus, depression may be expressed in differing ways depending on cultural background. For example, in East Asian cultures, sadness may be exhibited in the form of somatic complaints such as bodily aches, weakness, or fatigue. A higher prevalence of depression is consistently found among ethnic minorities, people of lower socioeconomic status, patients from rural communities, and immigrants. An evaluation of depression must take into consideration culture-specific presentations of depression to prevent misdiagnosis and/or delay treatment.

Cultural issues are clearly established as important factors that influence depression treatment outcomes through

treatment seeking, clinician-patient relationships, and level of engagement in treatment. Oncology professionals can learn about the characteristics of the patient, their family, and their culture from patient and family perspectives. A paradigm of cultural humility12 while providing care to minority individuals recommends the following:

- Openness- willingness to explore new ideas

- Self-awareness- being aware of one’s strengths, limitations, values, beliefs, behavior, and appearance to others

- Egoless- humbleness or throwing away ego

- Supportive interaction- positive human exchanges between patients and clinicians

- Self-reflection and critique- reflecting on one’s thoughts, feelings, and actions

Bottom Line/Conclusion

Individuals with cancer are at increased risk for depressive disorders throughout the cancer continuum, with notably higher prevalence rates than the general population. In addition to emotional well-being and quality of life, comorbid depression can directly and indirectly impact medical care. Overlap between symptoms of depression and cancer/treatment side effects underscores the need for oncology providers to remain vigilant to potential signs of depression, and to actively engage in processes for routine screening, assessment, and referral for treatment when indicated. Well-established clinical guidelines can help oncology professionals navigate the management of depression. Importantly, effective treatment approaches can significantly improve depression and quality of life and well-being in people with cancer.13

References/Links

- Endicott J. Measurement of depression in patients with cancer. Cancer. 1984 May 15;53(10 Suppl):2243-9. doi:10.1002/cncr.1984.53.s10.2243.PMID:6704912.

https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.1984.53.s10.2243

2.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160-174. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.900.840&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Fang F, Fall K, Mittleman MA, et al. Suicide and cardiovascular death after a cancer diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(14):1310-1318. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110307 https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1067.6992&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelinesâ) for Distress Management V.2.2024. ã National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2024. All rights reserved. Accessed April 3,2024. To view most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org.

- Krebber AM, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psychooncology. 2014;23(2):121-130. doi:10.1002/pon.3409 https://doi:10.1002/pon.3409

- Wakefield CE, Butow PN, Aaronson NA, et al. Patient-reported depression measures in cancer: a meta-review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(7):635-647. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00168-6 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(15)00168-6/fulltext

- Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, et al. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1605-1619. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611 https://dx.doi.org/10.1200%2FJCO.2013.52.4611 https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/hta23190#/abstract

- Li M, Kennedy EB, Byrne N, et al. Management of Depression in Patients With Cancer: A Clinical Practice Guideline [published correction appears in J Oncol Pract. 2017 Feb;13(2):144]. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(8):747-756. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.011072 https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2016.011072

Data Supplement: https://ascopubs.org/doi/suppl/10.1200/JOP.2016.011072/suppl_file/DS_2016.011072.pdf

- Serfaty M, King M, Nazareth I, Moorey S, Aspden T, Tookman A, Mannix K, Gola A, Davis S, Wood J, Jones L. Manualised cognitive-behavioural therapy in treating depression in advanced cancer: the CanTalk RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2019 May;23(19):1-106. doi: 10.3310/hta23190. PMID: 31097078; PMCID: PMC6545499. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta23190

- Li M, Kennedy EB, Byrne N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of collaborative care interventions for depression in patients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2017;26(5):573-587. doi:10.1002/pon.4286 https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4286

- Schulz-Quach C, Li M, Miller K, Rodin G. Depressive disorders in cancer. In: Breitbart WS, Butow PN, Jacobsen PB, Lam WWT, Lazenby M, Loscalzo MJ, eds. Psycho-Oncology. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2021:320-328.

12. Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural Humility: A Concept Analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2016 May;27(3):210-7. doi: 10.1177/1043659615592677. Epub 2015 Jun 28. PMID: 26122618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677

- Mulick A, Walker J, Puntis S, Burke K, Symeonides S, Gourley C, Wanat M, Frost C, Sharpe M. Does depression treatment improve the survival of depressed patients with cancer? A long-term follow-up of participants in the SMaRT Oncology-2 and 3 trials. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Apr;5(4):321-326. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30061-0. Epub 2018 Mar 12. PMID: 29544711.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(18)30061-0/fulltext