Self-care for the Health Professional

Introduction

In this chapter, we will define the importance and core components of self-care, using examples to enable oncology professionals to apply these principles.

Self-care can be defined as the practice of promoting emotional wellbeing and coping with challenges, by individuals and communities, independently and with external support.

If you’re experiencing feelings of depression, anxiety, or stress related to your workplace, you’re not alone.

- The myriad stressors oncology professionals face, including long hours, understaffed shifts, and witnessing patient suffering and death, make us vulnerable to compassion fatigue, burnout, and moral distress.

- Healthcare is facing a growing gap in trust and respect between frontline staff and management.

- Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 7-40% of healthcare professionals (HCP) reported compassion fatigue and burnout, and in 2021, reported rates were as high as 70% depending on medical specialty.

- More than ever, self-care for oncology professionals is critical.

Significance

- Essential HCPs are retiring earlier, retreating into management, and leaving the field entirely for less stressful jobs.

- Women, minority populations, and people with fewer social and financial resources are more negatively impacted by the added demands of the pandemic.

- However, history demonstrates that times of major social disruption have also created opportunities for significant structural change.

- Self-care in healthcare professionals translates into improved safety and efficiency in patient care and team interactions.

Major Principles, Categories, Concepts

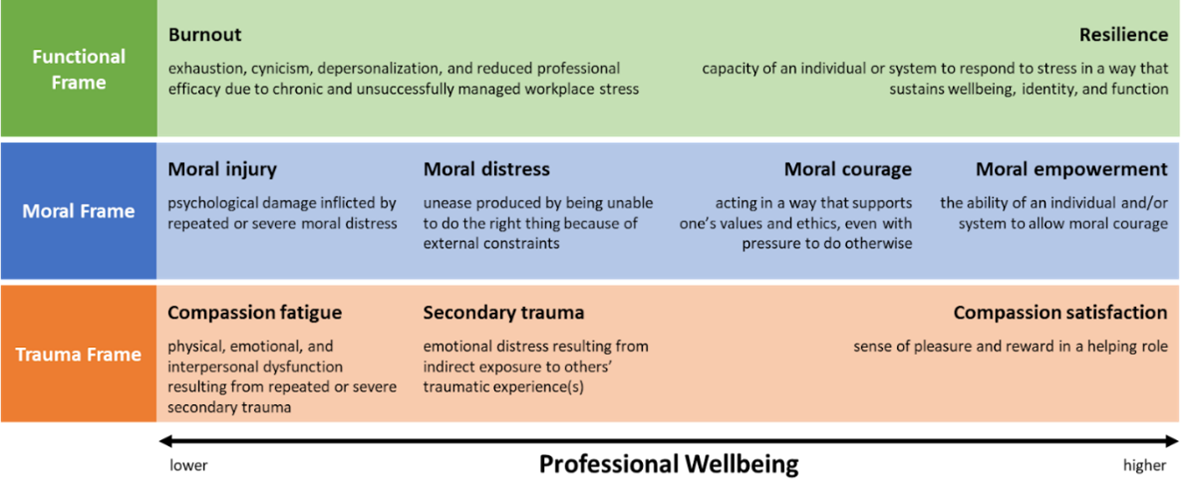

Self-care is foundational to the professional wellbeing of both individuals and teams. To move forward in self-care, it’s helpful to understand why we’re so likely to need it in oncology. We can understand struggle, despair, and dissatisfaction in work through multiple frames– not simply burnout, but also through moral and trauma-based concepts (Figure 1). Note that each struggle-based concept has a strength-based correlate (i.e., compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction).

Figure 1. Frames of Professional Wellbeing

Exercise: Think of a difficult clinical experience in the past month. What emotions did you feel in the moment; and now? Which frame (functional, moral, trauma) most resonates? Building a framework and language for how we struggle can help us process challenges and build resilience. For example, if we feel sad and scared after witnessing a patient code following a transfusion reaction, recognizing this as secondary trauma can validate our experience and make us cognizant of risks for compassion fatigue.

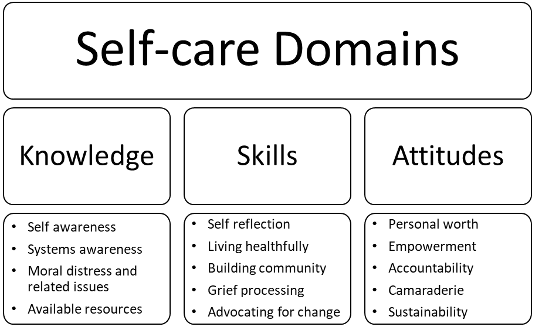

Practicing self-care isn’t just action. Like other learning endeavors, it encompasses domains of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, with examples of each in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Domains of Self-care

Exercise: In which domains do you already feel confident about your self-care? Where do you see a need for growth? Examples: navigating your healthcare system effectively, grief processing, self-protection, building empowerment for change, etc.

Possible Approaches/Best Practices

Individual Interventions

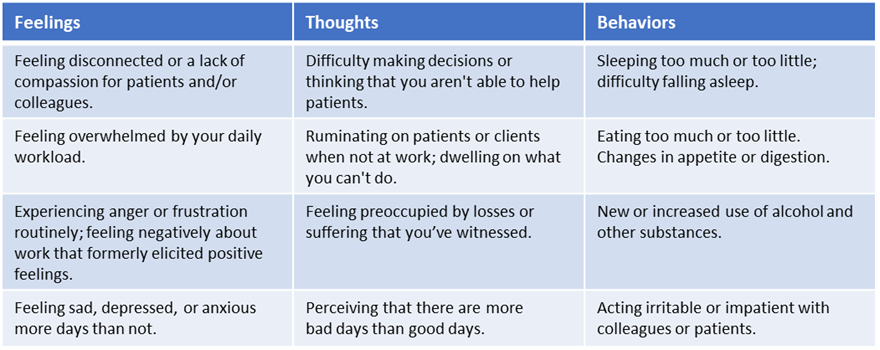

Identify Warning Signs of Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, and Moral Injury by Promoting Self-Awareness

Part of self-care is recognizing the symptoms of stress (Table 1) that you’re experiencing and then considering the coping skills that you’re relying on to manage them.

Table 1. Signs and Symptoms of Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, and Moral Injury

Click here to view table as PDF

Exercise: Consider if your coping mechanisms are impacting you positively or negatively. Are you managing in a manner that you are proud of? Are you processing difficult events or avoiding them?

Coping Skills for “On the Job” Stress Management

Practice self-compassion. It’s normal to have periods of feeling overwhelmed and exhausted by your work. When you evaluate your mental and emotional health, try to avoid feelings of judgment.

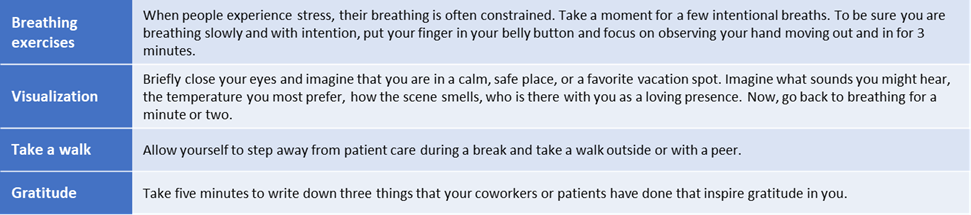

Use coping skills during your workday to help manage daily stress. The simple activities below (Table 2) can be completed during a five-minute break and can decrease your heart rate, blood pressure, and emotional distress.

Table 2. Coping Skills for a Five-Minute Break

Click here to view table as PDF

Exercise: Choose one of the coping exercises above and try it during your workday today. What do you notice afterward?

Self-care for Long-term Resilience and Mental Wellbeing

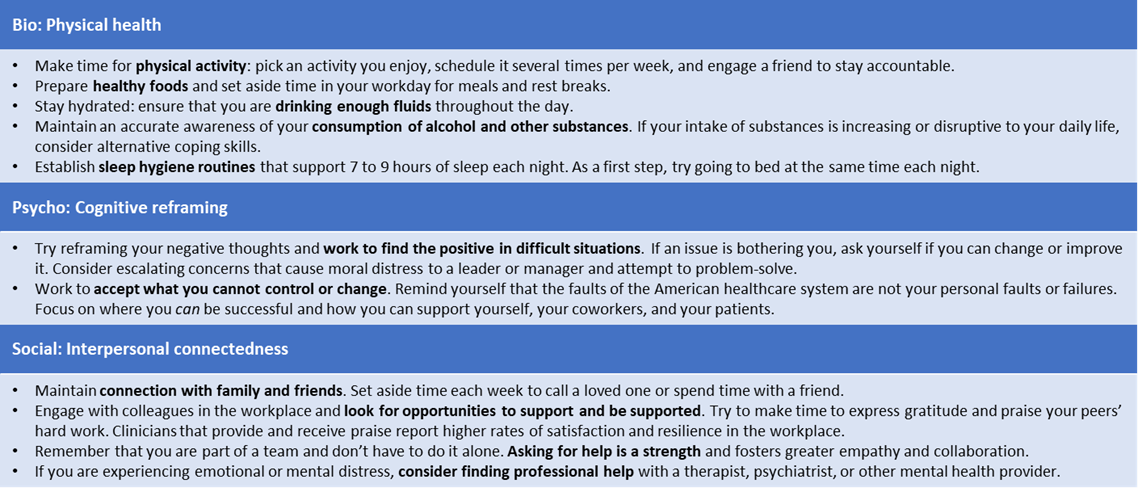

The ways you choose to manage the day-to-day stresses of your profession can greatly impact your ability to work in your field long-term. Do your best to pick healthy coping skills (Table 3) and build them into a sustainable routine.

Table 3. Healthy Coping Skills in a Biopsychosocial Frame

Click here to view table as PDF

Exercise: Which skills are already part of your routine? How are they helpful? What is realistic to add in the coming week? Commit to a small healthy behavior that you are certain you can do and do that! Then do that healthy behavior a bit more each week. A simple diary that you can review daily will help you document and feel the success needed to move forward and live better.

Team Interventions to Support Self-care

While individual self-care is essential, current models of resilience and wellbeing often send the messages: “do more,” or “cope harder,” which can ring hollow for individuals already overburdened by excessive demands and flawed healthcare and social systems. While individual self-care is necessary, we also need changes at the team and system level to support wellbeing.

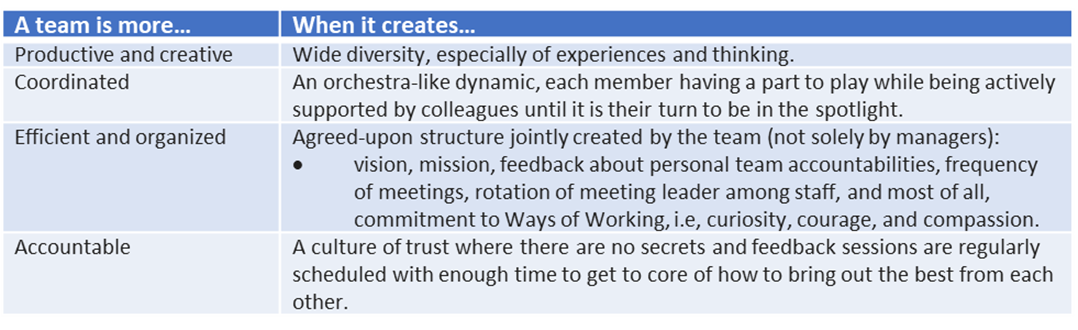

Current realities of healthcare teams:

- Comprised of individuals with differentiated roles, interacting with each other, working toward common goals. This diversity of professional identities also holds potential for conflict.

- Not a family. In reality, oncology’s high-stakes, emotionally charged, and exhausting dynamic engenders power struggles and tensions across personal, cultural, and professional identities.

- Fortunately, open and honest recognition and regularly scheduled courageous and compassionate discussions of these realties are robust opportunities to learn from each other and increase mutual trust, respect, creativity, and inter-professional accountabilities (Table 4).

Table 4. Features of Healthy Teams

Click here to view table as PDF

Exercise: Try asking these questions with colleagues at an upcoming team meeting.

- This is how I see me doing. How do you see me doing on this team?

- This is how you can bring out the best in me. How can I bring out the best in you?

Improving team meetings:

- Meetings should identify the goal(s) of the action-based meeting and based on specific value(s) (finances, hiring, patient care, self-care, etc.) on which decisions will be made. Information sharing alone is seldom a reason to have a meeting.

- It is periodically helpful to ask the group to estimate the financial cost of the meeting to ground the team of the value of their time and resources.

- Democratizing meetings is easily achieved by rotating the leader of the meeting and going in a circle with each member speaking or passing.

- Participants only speak again when it is their turn.

- Managers speak last.

Exercise: Your time is valuable. At your next meeting, ask each group member to guess the actual cost of holding the meeting, then ask if the use of such resources is appropriate. If not, how can you reduce meetings or change the structure to make the time worthwhile?

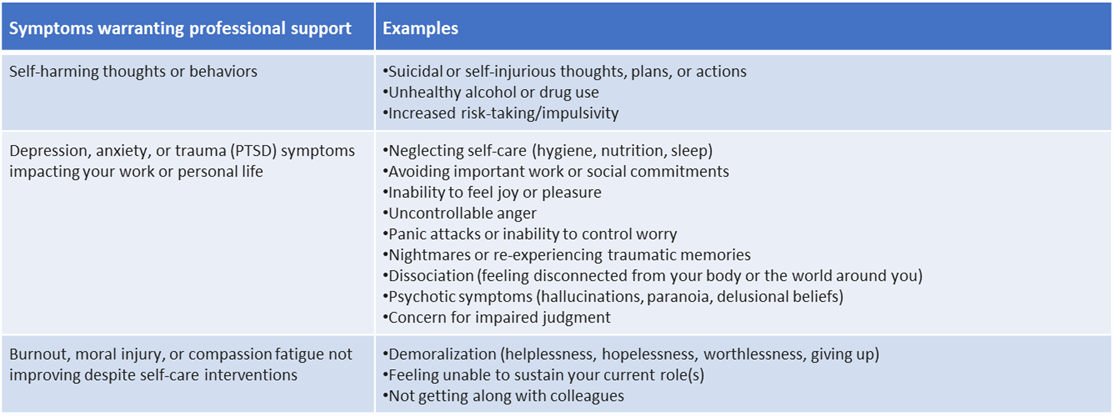

When to refer to specialty care

Sometimes, self-care requires more than just yourself. Even with our best efforts at productive coping, impacts of oncology work may contribute to significant depression, anxiety, PTSD, demoralization, or even suicide/self-harm. During periods when your coping skills are not adequately supporting your mental health, or you experience the following symptoms, reach out to a mental health professional for additional help (Table 5).

Table 5. When to Seek Mental Health Care

Click here to view table as PDF

Where to turn?

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255

- 24/7 support for mental health crises

- Your institution’s employee support/wellbeing initiatives

- Licensed mental health professionals: social workers, mental health counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychiatric advanced practice providers, via:

- Your primary care provider or insurer, workplace referrals, crisis/emergency services, and referral networks

Cultural Considerations

- BIPOC, minority, and minoritized healthcare professionals may face higher rates of PTSD, stress, and burnout due to traumatic impacts of racism, xenophobia, discrimination, microaggressions, and bias; COVID-19 has heightened these stressors.

- Being seen as “other,” cultural suppression, and undue burdens on minority colleagues to increase diversity pose barriers to wellbeing and harmony between personal and professional identity.

- We are all responsible for promoting safety, equity, inclusion, and cultural humility. Want to do more? Consider your own culture, reflect on potential biases, pursue Diversity/Equity/Inclusion training, join a peer group, seek or provide mentorship, and/or find opportunities to be an ally to minoritized colleagues.

- A workplace where employees can bring their “whole selves” to work fosters individual and institutional wellbeing and innovation.

Exercise: Do you feel you can bring your whole self to work? Could you ask a colleague this question? What can you do, and what can your institution do, if the answer is no?

Bottom Line/Conclusion

Oncology professionals provide complex and emotionally intense care within a strained and even broken healthcare system. Struggling in this system does not mean we are broken, but it does mean we must take personal responsibility for the self-care essential to thrive. We must each be accountable for our own physical and mental health, which begins by recognizing this need, valuing ourselves, and building realistic routines to promote wellbeing.

However, self-care isn’t simply individuals doing more or “coping harder.” Systems must evolve to make healthcare careers sustainable. Teams that value diversity, each member’s talents, collaboration, innovation, and time can improve the health of an organization through supporting its healthcare professionals.

References & Links

- Sanchez-Reilly, S., Morrison, L. J., Carey, E., Bernacki, R., O’Neill, L., Kapo, J., … & Thomas, J. D. (2013). Caring for oneself to care for others: physicians and their self-care. The journal of supportive oncology, 11(2), 75.

- Taplin, S. H., Foster, M. K., & Shortell, S. M. (2013). Organizational leadership for building effective health care teams. The Annals of Family Medicine, 11(3), 279-281.

- Loscalzo, S., Clark, K., Bultz, B., & Kotwell, J. Building supportive care teams: working together and self care. In: Breitbart, W., Butow, P., Jacobsen, P., Lam, W., Lazenby, M., & Loscalzo, M. (Eds.). (2021). Psycho-oncology. Oxford University Press.

- Osseo-Asare, A., Balasuriya, L., Huot, S. J., Keene, D., Berg, D., Nunez-Smith, M., … & Boatright, D. (2018). Minority resident physicians’ views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA network open, 1(5), e182723-e182723.

- https://org/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fnami.org%2FYour-Journey%2FFrontline-Professionals%2FHealth-Care-Professionals

- https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/type/skills_psych_recovery_manual.asp